| |

Community Art, Part II: The Nail Project

Halfway through Part I of my senior thesis, it became obvious I wasn’t going to raise a ton of money for materials. Still, I needed to think of a project that both involved every Geneseo student and faculty member on campus and fit the budget the community gave me. To me, involving each person meant having a token available for each individual, so I had to think of something I could get a lot of for cheap. Fairly immediately, nails presented itself as the best option.

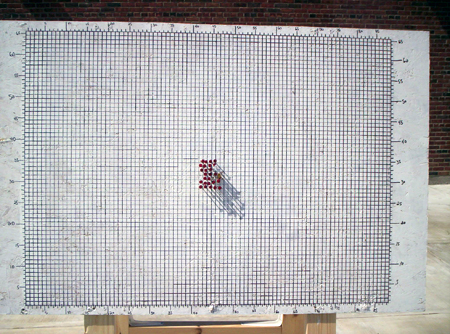

Here’s how it worked. I started by taking a picture of a Geneseo landmark. I uploaded the picture onto my computer and placed a grid on top of the image. The grid contained 5,720 boxes, equivalent to the number of students and faculty members at Geneseo. I examined each box of the image, noting what color/colors took up each box and creating a corresponding spreadsheet.

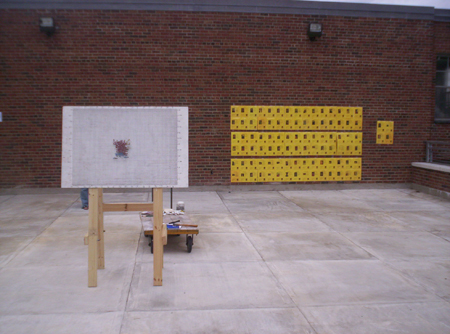

Next, I took a piece of plywood, constructed an easel for it, and put a 5,720-box grid on the board’s surface. Students and faculty would come up to the project, pick out a roofing nail and nail their contribution into a box on the board. Nailing finished, I’d look at the spreadsheet and tell them what color to paint the nail head. They painted, and as more people participated an image slowly revealed itself. As for the nature of the image, it was kept a secret until the last week of the project. I kept it a secret in order to create mystery and generate interest in finishing the image, as well as to continue along with the theme of trust featured in Part I of the work.

I had two spaces reserved on campus to display the work, one site for sunny days and one site for poor weather. I went out every school day for six weeks, trying everything to get people to stop and participate. It was rough going in the early days. Some people I talked to said they didn’t have enough time, which is understandable to a degree. Others flat out ignored me talking to them, even though there was no one else I could be talking to. I’d expect such behavior on the streets of New York, but not on the campus of a small liberal arts college. Still others cringed when I mentioned that I was doing an “art” project, fearful they’d have to do something bizarre or make something more elaborate than a stick figure. That was something I noticed throughout the project: how scared people were of exposing themselves to art-related ridicule and how utterly convinced they were that they had no artistic ability beyond the stick figure. Some people even asked me to paint their nail head – the monochrome, one brushstroke nail head – because they just knew they’d mess it up somehow. The power mental blocks can have over our perception of things is amazing.

As the weeks progressed, more and more people became interested in the project. A pleasant surprise was the demographic shift in participants. Where the beginning participants were mostly people I’d recruited on the spot, later participants, by and large, were referred to the project by friends. This made me realize it wasn’t about the people that weren’t nailing nails in, a fact my pessimistic mind was apt to focus on. Rather, it was about the people that were nailing nails in. They were the one’s talking about the project to friends, playfully prying about the identity of the landmark, and putting their support behind my idea. They were the one’s giving common purpose to my project, creating a community around my nail-ridden easel by sharing their thoughts with others and encouraging participation. It was through their efforts that a third community was fleshed out – one combining the size and identity of a larger community with the common ties* and trust of an immediate community.

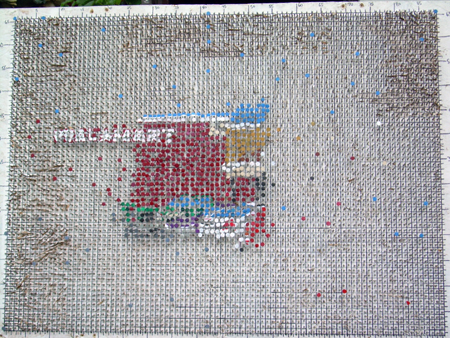

With less than two weeks to go in the semester, I held an unveiling for the identity of the landmark. About sixty people showed up to learn the image they had been creating for the past five weeks was…the Geneseo Wal-Mart. I opened the floor to questions.

Of course, the question on most minds was “Why Wal-Mart?” I could have picked any number of scenic Geneseo landmarks to be the recreated image. While the college clock tower is certainly a landmark, it would have generated very little thought on the part of the viewer. Wal-Mart is undeniably a Geneseo landmark. At the time of the project, the Wal-Mart in Geneseo was the largest in the state of New York and the second largest in the country, and remains the biggest hot-button issue of the college. As such, it was an image ripe for interpretation.

That being said, for the remainder of the project I made a conscious effort to remain neutral in expressing my opinion towards Wal-Mart. After all, there’s nothing inherently wrong with a picture of Wal-Mart. Rather, it’s the baggage viewers bring to the image that makes it good or bad. In acting this way, it was my intent was to give the viewer absolute freedom to draw his or her own conclusions about the work – to make their own art. All I did was give them the tools necessary to make it. Tools given in this instance were physical (the nails, paint, etc.) as well as conceptual (the repeated idea that my project focused on community), and allowed the viewer to extract personal meaning from the piece.

I find ceding the power of meaning to the viewer to be a wholly positive experience when making art. The alternative, producing one meaning for a work for viewers to take or leave, doesn’t sit well with me. That’s because I could talk to you for four hours about everything my art says, and while you’d now have a great idea of what I was going for, there would always be a barrier of articulation preventing me from fully conveying my ideas to you.

The limitations of language and matter stand like large, brick walls, and they’re not going anywhere anytime soon. I spend enough time bashing my head into the ramparts when I write, so when I make art I need to let go. With the open interpretation method, the viewer creates his/her own meaning for the piece, so there’s absolutely no loss in translation. Pieces of this nature have a 100% success rate in communicating meaning to the viewer, so the artist’s challenge becomes not communication but creation of a context that insures the communication is interesting/provocative/worthwhile. Finally, I enjoy this method because every time someone tells me what they think about one of my pieces, there’s a potential that I’ll learn something about my own work I’ve never considered. Sure, that could happen with one defined meaning, too, but the simple act of giving people permission to think for themselves can have wonderful consequences.

After the unveiling, I changed my methods slightly for the last week and a half. Where before I said to passersby, “Would you like to help me with a project?” now I said “So do you want to know what this is?” Now that all details of the project were revealed, I felt it was up to the community to decide if they wanted the image complete or not. Where before I asked people to nail in the center so a picture would be revealed, now I let people choose to either help finish the picture or represent themselves as individuals around the board. Isolated pixels appeared like stray confetti. Knowledge of the image evoked strange reactions from the students and faculty. Everything ranging from “I hate Wal-Mart, I’ll nail a nail” to “I love Wal-Mart, sure I’ll nail a nail.” I just smiled and continued to play neutral.

In the end, there were 776 nails painted, which means 776 participants or about 15% of the school. I must have interacted with over 1500 people when you count all the people that declined to participate. As for if I’m disappointed that the project wasn’t finished, I never seriously envisioned reaching completion. Getting a whole campus of college kids to do anything is impossible – you can’t even get them all to graduate. The idea was that there was the potential for everyone to join this new community if they so choose.

With school over and the project home with me on Long Island, the question became what to do with all the unnailed boxes. My thoughts were that since all these people had ample time to represent themselves and conceded that right, the right to represent them went to me by default. With this power in hand, there was a strong temptation to finish the image. I had done a couple of studies before the project started to see if the image would turn out on nail heads, but I had used only a few hundred nails. The resolution of a 5,720 nail image would be worlds superior, and I was very curious to see if community pointillism actually worked. But more powerful than that curiosity was the desire to see an aesthetic completeness in my piece. After all that work, never fully realizing your vision is a tough pill to swallow.

All that said, I never seriously considered completing the image. The true vision of the project was the creation of community, and in that respect that respect the work was complete. The board was the context necessary to create and express that community, and to finish the image would destroy any trace of that community’s existence. So instead of aesthetic completion, I chose to flip the board around and nail nails into the available boxes backwards. This method had it’s own aesthetic sensibility to it, and I appreciated it for the way it’s spiky nature perhaps spoke for silent members of the Geneseo community.

* I wasn’t sure “ties” was the best word to describe what I was getting at, so I wanted to unpack this idea a little more. I nixed several words to follow “common” before I settled on ties, namely “effort,” “interests,” and “connections.” The word “intimacy” even touches on what I want to get at, but I figured it would be too severe in this context. With the nail project, I see a common effort similar to being in a book club. I see a common interest similar to two strangers talking about the new building going up on the west side of town. I see common connection similar to learning your neighbor visits the same hairdresser as you. I see an intimacy similar to that feeling you have for the person on the bus listening to your favorite album – even if it’s a little too loud. Basically, “common ties” is meant to convey that deeper level of common experience that doesn’t naturally occur in a larger community.

For more images, visit the facebook page. For even more images, including day by day photos, friend me on facebook.

| |